How Low Can You Go?

There aren’t many topics that divides people in the fitness world more than squat depth and it’s relationship with injury. In this article I want to present an evidence-based perspective on this topic. I’ve decided to break it down by looking into the effect of squat depth on the areas of the body that people commonly complain about during squats.

KNEE

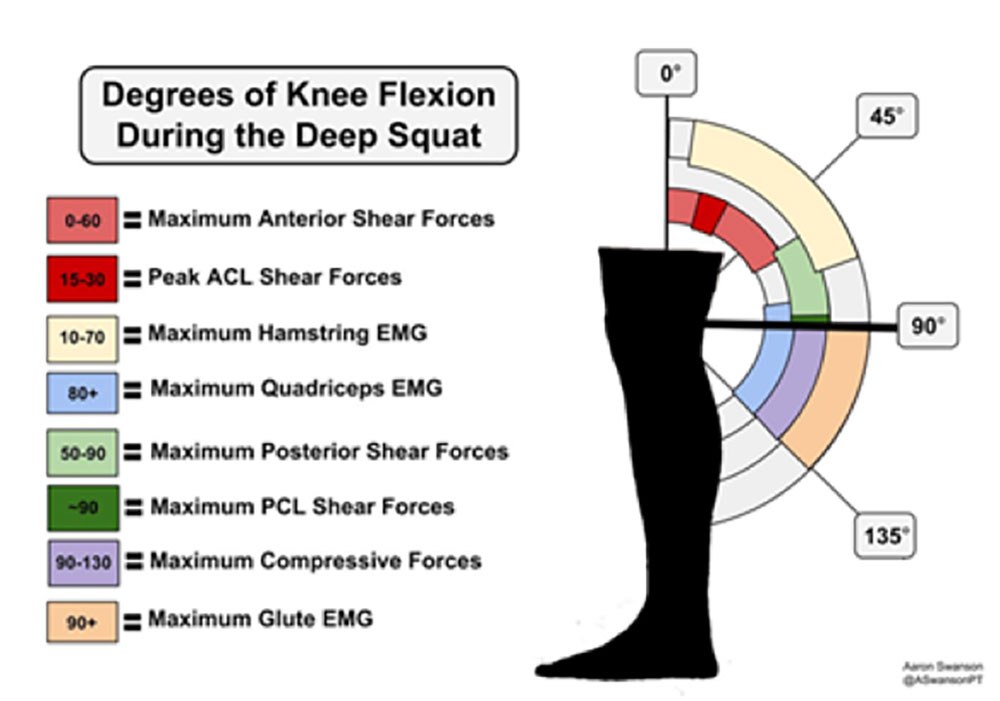

Squatting past 90 degrees is bad for your knees right? For the large majority of people, this is completely false. Forces on the ACL actually peak at partial squat depths and then reduce as squat depth increases and compressive forces increase to reduce shear force on the ACL.

But what about the meniscus and the patellofemoral joint (joint between your knee cap and your femur)? While compressive forces on the meniscus and PFJ increase as depth increases, if you don’t have any prior injury to these structures there is no evidence that squatting deep will cause injury to these structures. However, if you do have a meniscal tear or PFJ pain, it is a smart idea to limit your depth to pai

n-free ranges, and most of the time this will be above parallel (at least initially). If you have had issues with these structures in the past but are pain-free now, I would simply progress towards deep squatting but listen closely to your body and try bringing the depth back up if knee pain develops, and see if that helps.

What about those people with patellar tendon issues? As squat depth increases, the compressive load on the patellar tendon also increases. This can certainly aggravate the tendon, so it is worthwhile modifying squat depth for a certain period of time while completing your rehab exercises if you have a patellar tendinopathy. However, while completing this rehab, exercises like box squats, low bar back squats, and reverse lunges can provide much of the same benefits of high bar back squatting with far less anterior knee stress as they shift more of the workload to the hips. Give them a go and see how they feel, this could be a great way to maintain your squat strength while giving your tendons a bit of a break.

HIP (femoroacetabular impingement)

Ever felt a pinching sensation deep in your hip at the bottom of your squat? This is often due to impingement between the bony surfaces in the hip. And this impingement often becomes worse the deeper the squat. If this is you, then it may be worth bringing the depth up a little bit and working within your pain-free range until you have resolved the cause. FAI can be caused by structural abnormalities in the hip (in which case there is little you can do), suboptimal stance width and foot turnout for your hip structure (experiment with different widths and foot turnouts but generally a slightly wider stance and a little more foot turnout can work wonders for this), or issues with glute activation (the glutes can help to pull the femoral head posteriorly to reduce the impingement). I would also recommend people with FAI try front squatting for a little while, as there is less chance of impingement due to the reduced amount of hip flexion that occurs during this exercise.

LOW BACK

Ever racked the bar after squats and felt an ache across your low back, or had low back pain for hours/days after squatting? It’s possible that you may have squatted too deep and irritated the discs in your lumbar spine. When the pelvis posteriorly pelvic tilts (tips back) at the bottom of the squat as you run out of hip flexion range, this is commonly referred to as ‘buttwink’. Now while this may sound hilarious, it is associated with lumbar flexion (lower back rounding), which can place the discs under undue stress if the buttwink is excessive and loads are high. This is why I recommend squatting to the point at which a small amount of buttwink occurs, and not pushing any further. To delay the point at which buttwink occurs, I recommend working on your ankle and hip mobility as this is likely the most common cause of early onset buttwink.

In summary, optimal squat depth for injury prevention/management is highly dependent on your individual mobility and injury history. A depth that is appropriate for one person may not be for another, so don’t take a one size fits all approach.

If you are injury free, squat to a depth where you can maintain at least a mostly neutral pelvic position (i.e. allow a small amount of buttwink, but not too much). If buttwink happens well before your thighs are parallel to the floor, work on your ankle and hip mobility to help reach this depth, as there are some benefits to squatting this low over partial squatting.